HISTORY & LEGENDS

From heroes to haunting tales - we'll be featuring the best of our history, legends, and lore from The BRJ's archives, so check back often for new posts!

THE AMAZING CIVIL WAR RECORD OF WILLIAM VAN HORN

By C.G. Wolfe © The Black River Journal

Disease, exposure, crippling accidents and battlefield wounds – during a 16-month tour of duty, Private William Van Horn of the U.S. Colored Troops suffered every hazard known to a Civil War soldier and carried his scars home to Lamington, New Jersey.

Spending his time in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania and German Valley (now Long Valley), New Jersey during the early years of the war, William Van Horn was in his mid-thirties and a free black man when he joined the Union Army on May 9, 1864. Assigned to Company H of the newly organized 43rd regiment of the US Colored Troops, he saw his first major action less than three months later.

Since mid-June, the Union Army’s campaign to capture the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia, had ground to a halt around the defenses of Petersburg, a vital railroad center 24 miles south of the city. Both sides were locked in a bitter siege that foreshadowed the type of grim trench warfare later seen on the fields of World War One.

In an effort to break through the Confederate lines, a Lt. Colonel named Henry Pleasants devised a daring plan. He had overheard a man in his regiment, one of the many Pennsylvania coal miners in his command, brag that he could blow up an enemy position by tunneling underneath it. Pleasants brought the plan to his commander, Major General Ambrose Burnside, who secured permission from the commander of the Union forces, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, to give it a try.

In just over a month, the coal miners made good on their boast and dug a 600-foot tunnel that led directly underneath a section of the Confederate defensive works. Here, they packed two galleries with 8,000 pounds of explosives and waited to light the fuse.

The plan called for an attack to be made through the gap in the enemy’s line that would be created by the explosion, and William Van Horn and the 43rd Regiment were part of an all-black division that was chosen to spearhead the assault. The division spent a week before the detonation rehearsing the plan of attack until each man knew exactly what to do – which was to move quickly after the mine exploded, sweep around the crater caused by the explosion, and attack the enemy flanks to widen the gap in the enemy line. The all-black division was to be followed by three white divisions, which would move unopposed to the high ground behind the demolished trenches, leaving a clear road to Richmond.

On the eve of the assault however, Grant made what would turn out to be a fatal decision. He ordered Burnside to replace the all-black division with one of the white divisions, none of which had rehearsed for the initial attack. Grant would later claim that he didn’t want to be exposed to criticism for placing the black troops at the head of a dangerous mission, if the attack should fail. A despondent Burnside chose the replacement division by drawing straws.

At 4:45 a.m. on July 30, the four tons of powder were detonated and an awesome explosion tore a hole 170 feet long, 80 feet wide, and 30 feet deep in the Confederate earthworks. Nine companies of rebel soldiers were hurled into the air – 300 of them were instantly killed, maimed, or buried alive. Confederate troops on either side of the maelstrom fled their lines in panic and left a 400-yard gap in their defenses.

After stopping to gaze in awe at the mammoth hole and house-sized clods rent from the earth, the lead Union division, whose commander was hiding in a bombproof swigging rum, finally attacked. But instead of fanning out around the rim and attacking the enemy flanks, as the black division had rehearsed, they plunged into the crater. Burnside sent in the two remaining white divisions to follow up the initial attack, but like the lead division, they also charged into the crater. When the black division was finally ordered in, they advanced in good order, chanting “We look like men a-marching on, we look like men of war!” They swung around the crater to attack the enemy flanks, just as they had rehearsed, but it was too late.

By this time, the Confederates had regrouped and counterattacked, sealing the hole in their line and pouring a deadly fire down into the divisions that sat like fish in a barrel at the bottom of the crater.

The black troops, including the 43rd Regiment, fought gallantly, losing a third of their men to galling artillery and infantry fire that raked their front and flanks, until they were finally forced to withdraw. Confederate soldiers, outraged at the sight of colored troops, killed many of the black soldiers that were left behind and tried to surrender.All ensuing attacks were cancelled and Burnside was ordered to withdraw his men, a move that was accomplished, but easier said than done. In the end, the Union lost almost 4,000 men and the Battle of the Crater went down as one of the worse managed battles and greatest missed opportunities of the war. The 43rd Regiment lost 123 men at the Crater. William Van Horn emerged from the fight unscathed, but unfortunately his luck would not hold out much longer.

From August 18-21, the 43rd was involved in operations against the Weldon Railroad, which linked Petersburg to North Carolina. William Van Horn was building log breastworks to bolster the Union line when he slipped and fell, severely injuring his back and causing kidney problems that would chronically plague him.

By late September, he was back on his feet and during the next month, the 43rd participated in operations at Poplar Grove Church, Boydton Plank Road, and Hatcher’s Run. While on picket duty near Fort Harrison Van Horn was shot through the left groin area, the bullet passing through his thigh and entering his other leg. Left with a permanent limp, he recovered and soldiered on, returning to duty with the 43rd, who were occupying a peninsula between the James and Appomattox Rivers in Virginia, known as the Bermuda Hundred. Here, sometime during the cold, wet winter in February 1865, Van Horn suffered crippling frostbite to both feet, battled a severe cold, and developed a bout of “scurvy” that left him blind in his right eye.

The 43rd continued to participate in operations that led to Robert E. Lee’s eventual surrender at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865. In June, the 43rd regiment was transferred to the department of Texas and served on the Rio Grande, opposite Mattamoras, Mexico. Van Horn was treated for scurvy again, but amazingly continued to serve until he was discharged on November 30, 1865 in Philadelphia.

William Van Horn went home to the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania for a few years, before returning to New Jersey, where he resided in Bound Brook for a few months before settling in the Lamington area of Bedminster Township, in Somerset County. William found work as a farm hand and married Annie Wortman at a service performed by the Reverend P.M. Doolittle, pastor of the Reformed Dutch Church at North Branch.

Van Horn carried the physical reminders of the war for the rest of his life, which eventually left him “unable to do half the work of an able bodied man.” In addition to the wounds and sicknesses reported in his war record, a later examination by Dr. J. Beekman uncovered a “severe injury on the back of the head near the base of the brain.” William stated that the scar was caused by a sabre cut he received during one of the battles. It may have been the cause of the epileptic seizure that claimed his life on August 30, 1887 at the age of 58. William Van Horn is buried in the Lamington Black Cemetery. On Cowperthwaite Road, in Lamington.

The Lamington Black Cemetery

Wooded and serene, simple white crosses and weathered stones mark some of the graves of former slaves and free blacks at The Lamington Black Cemetery, while others lay beneath uninscribed fieldstones or are only identified by tell-tale depressions in the earth. Among the 97 verified sites, which include five veterans of the Civil War, it is believed that Cuffy Barnet, a lay preacher in the Bedminster African American community, known as “The Lamington Black Saint,” is buried in one of the 63 graves of the unknown. Cuffy and his wife Amber, were the slaves of Dr. Oliver Barnet, a physician in nearby Oldwick, and were freed in 1825, after Barnet’s widow’s death. It’s likely that Cuffy presided over many of the burials at the Lamington Black Cemetery as, according to Volume 8, of The Somerset Historical Quarterly (1919), Cuffy “generally attended all funerals of his own race in the Lamington neighborhood and, when no ordained minister was present, he offered appropriate prayer at the grave.” All but abandoned and forgotten over time, the cemetery was rediscovered in the late 1990s and a community restoration project eventually led to its placement on the National Register of Historic Places and a rededication in 2001, which included a 21-gun salute by an Army Honor Guard and culminated in a lone bugler playing “Taps” over the graves of the Union Veterans of the Civil War.

The grave of William Van Horn in the historic Lamington Black Cemetery (Lee Wolfe)

the minuteman from black river

By C.G. Wolfe © The Black River Journal

"That for the purpose of effectually carrying into execution the recommendation of the Continental Congress respecting the appointment of minute-men, four thousand able-bodied effective men be enlisted and enrolled in the several counties in this Province … who shall hold themselves in constant readiness, on the shortest notice, to march to any place where their assistance may be required for the defense of this or any neighboring colony." New Jersey Provincial Congress “plan for further regulating the Militia" 16 August, 1775

Though the first shots of the American Revolution had been fired at Lexington Green in the far-off colony of Massachusetts, the war would soon arrive in New Jersey, where an estimated 300 battles and skirmishes would be fought during the country’s struggle for independence. In the predominantly pro-patriot Morris County, the village of Black River, now known as Chester, prepared for the coming conflict. Three of the old “Indian Forts;” the Goss house, the Jared Haines house, and a building on the Guerin farm, along with a fourth stone house built by William Corwin, were designated as safe houses for the women and children to gather in case of an attack. A signal system consisting of hilltop beacon fires (the reason for so many “Beacon Hill Roads” in New Jersey) and cannons used as alarm guns, stretched from New York through New Jersey, ready to pass the alarm to the citizen soldiers of the militia, and the legendary “minutemen.”

Morris County was among the first in the colony to create minutemen companies, which were made up of the youngest, strongest men in a local militia unit. Unlike regular militia, in which every able bodied man from the ages of 16 to 60 were required to serve by law, the minutemen were volunteers. They trained more often than the militia, sometimes two to three times a week, and were expected to keep their arms with them at all times so that they could march at a minutes notice. On the fringes of Chester Township, John Emmons (1764 - 1833), who lived with his family in a simple log cabin that stood west of Route 206, just north of Lamerson Road, was one of the young men that waited for the call to war.

Frances Greenidge, in her 1974 book, Chester, New Jersey: A Scrapbook of History 1713-1971 (Chester Historical Society) writes that “One Black River Minute man was young John Emmons – still in his teens. He served from Somerset County, though later his farm was considered ‘just inside Morris County’… John’s granddaughter, Ruth (Emmons) Lamerson, years later, delighted in showing her grandchildren ‘exactly where’ young John ‘placed his gun in the fence corner’ on a certain day in 1779 before starting to plow the ‘upper field.’ She told of his hearing ‘the shot down in the valley … calling the men to duty,’ and showed ‘exactly where he hitched his horses to a tree’ as he ‘grabbed his gun and raced to the assembly point!’”

John Emmon’s call to action was more likely in June, 1780, in response to the British incursion that led to the battle of Connecticut Farms (now Union Township). New Jersey militia gathered from as far as Hopewell, to harass and ultimately help to drive off the enemy, who were attempting to attack Washington and the Continentals in their camp at Morristown. Two weeks later, the British mounted another expedition against Morristown, which culminated in the Battle of Springfield. Once again, the British were surprised by the number of militia that turned out to oppose them, and as they withdrew for a second time, they were sniped at by New Jersey militia men, who kept up a harassing fire from the cover of the woods. Washington wrote that the New Jersey militia “…flew to arms universally and acted with a spirit equal to anything I have seen in the course of the war.”

The Emmons log cabin in Chester, known in later years as the Wyckoff Cabin, survived until the 1930s and was known to be the last colonial log cabin in the area. In the twilight of autumn, when the thick green canopy falls and lets the sun through again and the dense underbrush and tangled vines subside, the remains of the cabin’s foundation reappear. It’s the only marker to a site that may have played an even greater role in Chester’s history than just the humble homestead of a local minute man. Chester historian Joan Case, in her book, Then and Now: Chester (Arcadia Publishing 2005), wrote that “It has been noted in a letter in the Washington’s Headquarters library, in Morristown, New Jersey, that George Washington himself stayed in a log house one mile south of Chester. It is believed to have been this log cabin.”

The Emmons / Wyckoff Cabin

The above undated photo of the Emmons/Wyckoff Cabin comes from the collection of the late Dorothy (Wortman) Metzler.

As rough as hell

By C.G. Wolfe © The Black River Journal

This article first appeared in our May 2001 issue as a special Memorial Day feature. We've had many requests for it over the years and are happy to be able to bring it to you again through our "Best of The BRJ" archives.

By the summer of 1942, the military juggernaut of Imperial Japan had won a vast empire for the tiny island nation. The borders of its far-flung conquests ran east from the Gilberts and Wake Island and west to the Soviet/Manchurian border through Burma and India. They reached north to the Aleutians and south to Sumatram Java, Timor, half of New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. It was on this southern boundary that Japan now prepared for its next offensive – to meet the looming Allied counterattack.

After being checked in the east at the Battle of the Coral Sea, and then defeated at the naval battle of Midway, Japan looked south for further expansion and to stop the Allied build-up taking place in Australia under American General Douglas MacArthur.

Key to Japanese hopes of taking Port Moresby and the rest of New Guinea, was the fetid, pestilent island of Guadalcanal in the southern Solomons. Here, on the torrid jungle island, the Japanese were building an air base to accommodate the bombers that would be essential in supporting the offensive in New Guinea and cutting the crucial supply lines of troops and material from America.

The Americans also recognized the importance of Guadalcanal and the potential threat of a Japanese air base there. On August 7, exactly eight months after Pearl Harbor, the Marines of the 1st Division (the old breed), led by General Vandegrift, launched the first American amphibious assault of the Pacific campaign. They caught the Japanese defenders of Guadalcanal completely by surprise.

The Marines achieved all of their immediate objectives, including taking the nearly completed air base, which they renamed Henderson Field, in honor of a Marine pilot killed at Midway. The Japanese defenders, who were mainly construction workers building the airstrip, retreated into the jungle, leaving behind construction equipment, building materials, and stores of food. They also left their breakfast, which the Marines found still warm, on the abandoned tables of the mess hall.

Though things were going well on land, the Navy, in a controversial move, pulled out of Guadalcanal in the face of the Japanese naval threat, and were dealt a crushing blow during the Battle of Salvo Island. The Marines were left stranded without most of their heavy guns, 1,000 reinforcements, and half of their food supplies. By living on the captured Japanese stores (mainly fish, rice, and soy beans), they held on until a tenuous sea-borne supply line could be maintained, and somehow they managed to get the airfield up and running. The first airplanes of what would be known as the Cactus Airforce (for Guadalcanal’s code name) arrived to the sound of the cheering “mud” Marines, on August 20.

The Japanese were stunned initially, but they were also determined to retake Guadalcanal and Henderson Field. On the same day that planes began landing at Henderson, Japanese Colonel Kiyona Ichiki launched an assault on the defensive perimeter around the air field in a two-day engagement known as the Battle of the Tenaru River (it was actually the Ilu River). The Japanese however, greatly underestimated the American strength on Guadalcanal. Ichiki’s 800-man force was annihilated. Colonel Ichiki himself, in a futile last stand, burned the unit’s colors and committed harakari.

On the night of September 12 through the morning of the 14th, the Japanese attacked the Henderson Field defensive perimeter again. This time, 5,600 men of the Japanese 35th Brigade attacked the Americans along a low ridge known afterward as “Bloody Ridge.” Here, a small battalion of Marine Raiders, led by Colonel Merritt Edson (who received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions), tenaciously held back the Japanese attack, inflicting 1,200 casualties on the enemy. Finally, the Japanese decided that only a large force could dislodge the stubborn Marines. During September and October, they shipped another 20,000 soldiers to the small, festering island of Guadalcanal for the final assault.

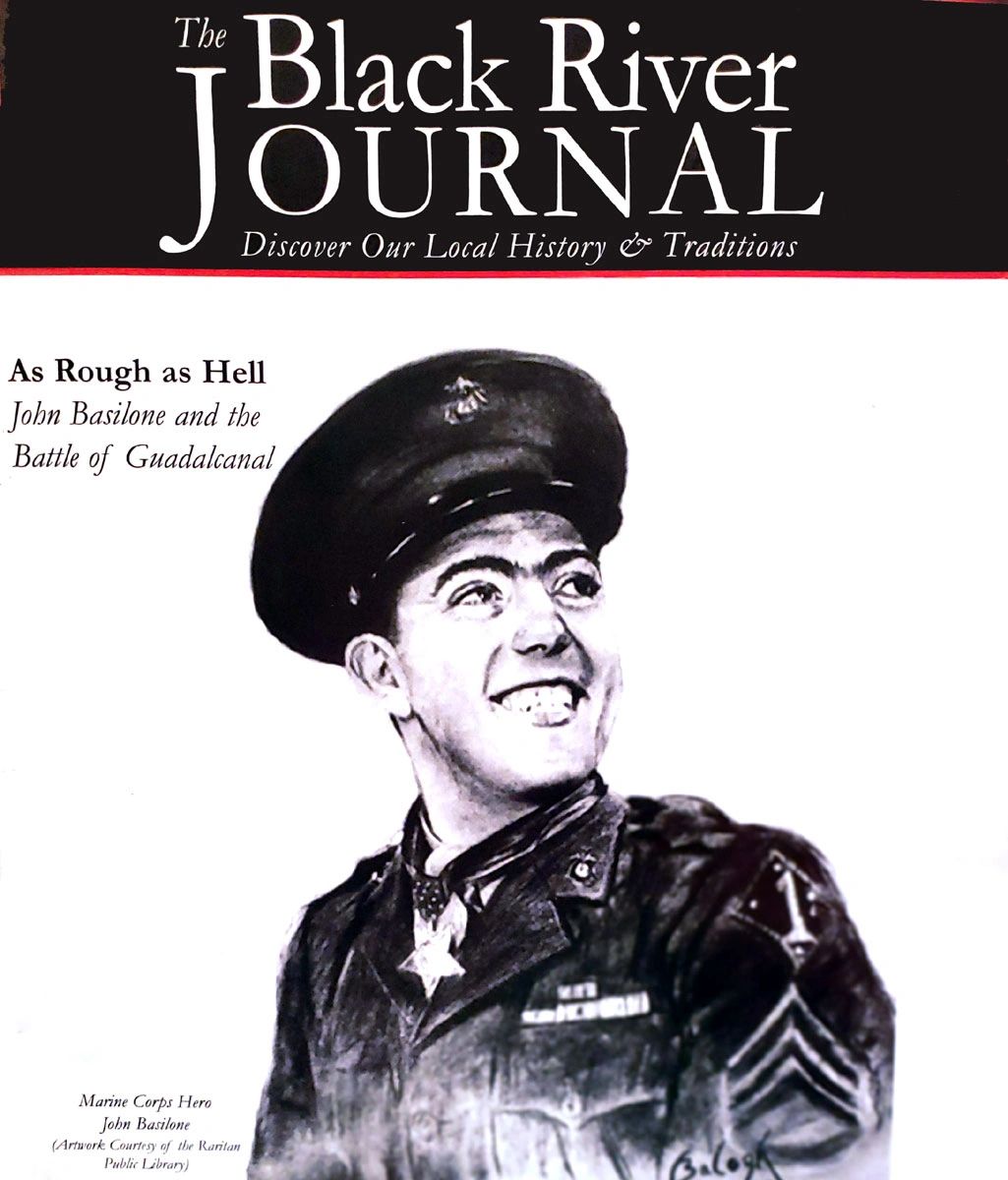

A Marine’s Marine

The Marines were also receiving reinforcements on Guadalcanal, including Lt. Colonel Lewis “Chesty” Puller’s 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. Among these Marines was Sergeant “Manila” John Basilone, a section leader in a weapons company, from Raritan, New Jersey. A big, swaggering Marine with a devilish smile, John Basilone would find the adventure he had long been seeking on Guadalcanal. He would also be the first enlisted Marine in World War II to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Basilone was a big, black-haired, handsome kid with an infectious smile and a “twinkle” in his dark eyes. The son of an Italian immigrant and an American-born mother, John’s adventurous, fun-loving nature made him stand out from his nine brothers and sisters. Always joking and laughing, John’s high spirit and talkativeness often exasperated the nuns at St. Bernard’s Parochial School in Raritan, but his charm and winning smile always kept him out of trouble.

John was restless for adventure, and it was clear no job was going to hold him in New Jersey. In 1934, just before his 18th birthday, he told his mother, “I’ll find my career in the Army,” and he convinced her to sign his enlistment papers.

Basilone had an aptitude for the military, especially machine guns. He could fire them with deadly precision and fieldstrip and reassemble them blindfolded. He spent four years in the Army, including two years with the US 31st Infantry in the Philippines. Besides being a crack soldier, John was also a champion Golden Gloves boxer. This reputation for toughness, combined with his outgoing, good nature, and legendary storytelling, made him a local celebrity on Dewey Avenue, earning him the nickname “Manila” John.

When Basilone returned home to Raritan, his mother hoped he would finally settle down and start a family. But “Manila” John was still restless. His job driving a truck for Calco Chemical Company in Bound Brook soon had him dreaming of adventure and longing for his old military life. In 1940, with the dark shadow of war creeping towards America, John told his mother, “the Army’s not tough enough for me,” and he joined the United States Marine Corps.

Basilone was assigned to a weapons company and was soon back with his old love – machine guns. He was a rugged, aggressive Marine but he looked after the men in his section and showed a natural ability to lead and inspire; he was a Marine’s Marine.

Marine, You Die Tonight

On the night of October 24, the 600 men of the Chesty Puller’s 1st Battalion stared across the mowed-down fields of Kunai grass, waiting for the Japanese onslaught they knew was coming. They were spread out along a 1,000-yard front, on a low rise, known as Lunga Ridge. Crouched in muddy foxholes in a steady rain, they knew there was nothing between them and the thousands of Japanese soldiers massing to their front, but the pitch-blackness of the jungle night and a thin perimeter of barbed wire adorned with shell fragments. (The shell fragments rattled and clanged if anyone disturbed the wire, a trick learned by Chesty Puller, while fighting in the “Banana Wars” in Nicaragua.) Anchoring the line was Sgt. John Basilone, his 14 men, and four heavy, Browning water-cooled machine guns of his section, divided evenly in two foxholes.

As the Japanese of the veteran “Sandai” Division (the butchers of Nanking) began slithering across the rotting jungle floor and up the ridge, the clanging of the shell fragments on the barbed wire could be heard by the Marine line. At 9:30 pm, the telephone rang at the battalion command post; it was one of the Marine listening outposts located 1,000 yards in front of the main line. The outposts were now completely surrounded and as Colonel Puller put his ear to the receiver, a tense voice whispered from the other end, “Colonel, there are about 3,000 Japs between you and me!”

Soon, the stillness of the night and the rhythmic pitter-patter of the rain were shattered by menacing screams from the Japanese soldiers who taunted the Marines from behind the black jungle curtain: “Marine, you die tonight,” and “Blood for the emperor.” Undaunted, a Marine voice bellowed back, “to hell with your emperor, blood for Eleanor and Franklin!” This was followed by laughter and a barrage of appropriately aimed obscenities tossed from the Marine line.

Suddenly, the night exploded in a frenzied, shrieking mass of Japanese soldiers who hurled themselves at the barbed wire perimeter, flinging dynamite and grenades to clear their way. Puller roared the order to “Commence firing!” and the Marine line burst into a fiery, stabbing sheet of machine gun and rifle fire that ripped into the Japanese assault wave.

Dead Japanese soldiers quickly piled up along the perimeter wire under the devastating hail of Marine lead. But the disciplined and fearless Japanese soldiers continued charging, like a wailing fury, and used the corpses of their dead comrades to bridge the barbed wire as they over-ran the isolated Marine positions in their ferocious bid to retake Henderson Field.

John Basilone’s section was blazing away at the oncoming enemy and trying desperately to plug a gap in the wire. John was on his left flank, when one of his men rushed over and frantically reported that the right flank had been overrun. Five of the seven Marines there were dead or wounded, and both machine guns were “busted.” Instinctively, Basilone grabbed one of the machine guns from the left flank, which was red-hot from the incessant firing, and hefted it over his shoulder. Ordering two of his men to follow him, he dashed off towards his imperiled right flank. Halfway there, they ran into eight Japanese soldiers. They managed to kill all of them in a brisk firefight and got through to the isolated foxhole. Basilone immediately set up his machine gun and put it into operation. Of the two guns that were out of action one was completely destroyed, but the other was only jammed. Lying at the bottom of the foxhole in the dark, in the middle of a desperate battle, Basilone coolly stripped the gun, cleared the jam, and swung it into action. By this time, there were only two other Marines left in the foxhole with him. He put one on each of his flanks and began firing both machines gun himself. He would fire one gun, then roll over to the other to let loose a burst, and then roll back. He kept up continuous fire as the Marines on his flanks blasted away with rifles and pistols.

Throughout the battle, enemy soldiers broke through to Basilone's position. He managed to shoot them down at the last second with his .45 pistol that he kept on the ground by his side. Several times during the battle, when his men got low on ammunition, John would dash the 150 yards (now in enemy hands) back to the supply base. There, he would fling a hundred pounds of ammo belts on his back and fight his way back to his beleaguered men with nothing but his pistol, a machete, and grim determination.

All that night, without sleep, food, or water, John Basilone and the Marines of the 1st Battalion, repelled the bloody Japanese “banzai” attacks. Outlined in the eerie flickering of muzzle flashes, grenade explosions, and the ghostly green glow of Japanese flares, they cut away with their Brownings, burning out there riflings as the machine gun barrels glowed red hot from the incessant firing. When the shrieking waves broke through, the Marines clubbed them with rifles, stabbed them with their K-Bar knives, and threw them back in savage hand-to-hand combat. In the morning, some help came in the form of reinforcements from an army battalion from the 164th Regiment (scrappy North Dakota and Minnesota farm boys spoiling for a fight). The line was bolstered for another night of murderous and relentless onslaughts.

Finally, after grinding away at the Marine position for over 72 hours with over 15,000 men, the Japanese commander, General Murayama, called off the ill-fated attack and retreated back into the jungle after sacrificing 3,500 of his brave and loyal soldiers.

Death before Dishonor

After the Japanese retreated, the defenders of Lunga Ridge emerged from their foxholes like refugees from a tempest rising from their storm cellars to behold the devastation. The jungle was torn to pieces from bullets and explosions as if a tornado had touched down. The carnage from the gruesome work they had wrought on the relentless enemy was strewn in ragged heaps all around them.

In a hellish scene of war’s brutality, over 1,000 Japanese soldiers littered the narrow, smoking field, frozen in the ghastly throes of death. In front of the machine gun positions, the dead lay in bloody piles two and three deep. Along the shattered barbed wire perimeter, mangled corpses hung from the twisted coils like victims in a ghoulish slaughterhouse.

In the midst of the human wreckage, standing barefoot among the thousands of brass shell casings that carpeted the deck (one machine gunner reportedly fired over 26,000 rounds alone), was Manila John Basilone. His face was hollow with exhaustion and smeared in black soot from sweat and burnt gunpowder. A Marine who served with him recalled that “his eyes were red as fire” red and his beloved .45 was tucked in his waistband. The sleeves of his muddy shirt were rolled up to his shoulders revealing a fitting tattoo. The image was a dagger plunged into a human heart, with the words “Death Before Dishonor.”

Japan’s Doom Was Sealed

The bitter struggle for Guadalcanal would continue for several more months. The irreplaceable losses suffered by the Imperial Navy in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal made it impossible to reinforce and supply their troops. Finally, the Japanese command reluctantly retreated from the embattled island. During the nights of February 5, 6, and 7, the Japanese evacuated General Hyakutake, who had been denied permission to lead his men on a final suicide assault, and 13,000 of his haggard, starved, malarial men from the place they called “the island of death.” Of the over 40,000 Japanese troops sent to Guadalcanal, only 23,000 came out.

The battle of Guadalcanal was a decisive victory for America and was a turning point in the war. As well as dispelling the myth of Japanese invincibility, it put Japan on the defensive in the Pacific for the rest of the war. As Japanese Admiral Tanaka stated, “There is no question that Japan’s doom was sealed with the closing struggle for Guadalcanal.”

Gunnery Sergeant Basilone

John Basilone received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on Guadalcanal and was promoted to Gunnery Sergeant. He accepted his medal saying that each man who died on Guadalcanal owned a piece of it. Of the battle itself, he later commented, “it was rough as hell….”

In July of 1943, John Basilone returned home to a hero’s welcome and the loving arms of his proud family. A huge parade was organized in Raritan, followed by a reception at “Cromwell Estate,” the home of heiress, Doris Duke. 20,000 people turned out to see the hero of Guadalcanal and present him with $5,000 in war bonds, purchased by the grateful citizens of Raritan and Somerset County.

Afterward, John went on a ten-state War Bond tour, making appearances, giving speeches and, as he said, being shown around like a “museum piece.”

He was offered a commission, but turned it down, proud of his new rank of Gunnery Sergeant. As a Congressional Medal of Honor winner, he could have spent the rest of the war selling war bonds or training troops. Instead, he asked for a transfer back into a combat zone, saying that he couldn’t think of the Marines marching up Dewey Avenue in Manila without “Manila” John Basilone.

John got married in July 1944 to a woman Marine Sergeant named Lena Riggi in San Diego. Two months later, he shipped out as a platoon leader with the 27th Marines of the new 5th Division.

The Black Ash and Sand of Iwo Jima

On February 19, 1945, John Basilone and his machine gun platoon hit “Red Beach 2” on the volcanic island of Iwo Jima. Iwo Jima is a tiny island of eight square miles that would prove to be hell on earth for the Marines who battled through its thick, black sand to get at the Japanese defenders who had turned the island’s labyrinth of caves and tunnels into a veritable fortress.

As Gunnery Sergeant Basilone was leading his men inland, in the face of deadly machine gun fire and screaming artillery barrages, they ran directly into a camouflaged, concrete, Japanese blockhouse concealed in a sand dune. It stopped them cold with vicious, point blank canister shot.

In the face of this maelstrom being hurled at them from the blockhouse and an intense mortar barrage that whirled around them, Basilone had his men dig in and began burrowing his way alone through the scorching black sand towards the enemy. Exposed the entire way to enemy fire, he reached a position directly on top of the blockhouse. With satchel charges and grenades, he single-handedly destroyed the fortified position and killed all of its defenders.

Standing on top of the smoking blockhouse, he turned towards his men and pulled his K-bar knife. He began waving it defiantly at the Japanese, urging his men forward and taunting the fleeing enemy troops.

As they cleared the blockhouse and began moving towards their objective, Airfield No. 1, they came across and American tank that was trapped in a minefield and being raked by enemy mortars and artillery. Again, Basilone told his men to take cover and dashed out alone into the minefield. As the ground around him shook and convulsed with explosions, he carefully picked his way through the minefield and guided the tank crew to safety.

As they continued inland, Basilone led his platoon on to their objective. They had just reached the edge of the enemy airstrip at Airfield No. 1 under a steady rain of whirring mortar fire, when an incoming round burst at John Basilone’s feet. With no time to react, the searing shrapnel from the direct hit tore into John and four other men around him.

The corpsmen were unable to save Manila John, as his vital, young life spilled out onto the torrid black ash and sand of Iwo Jima. As he lay dying from his gaping mortal wound, he still had that irrepressible twinkle in his eyes and managed to flash his unforgettable winning smile one last time, to reassure his stunned men as they came streaming by.

John Basilone would posthumously receive the Navy Cross for the bravery and leadership he demonstrated that day on Iwo Jima. He was only 28 years old.

John Basilone was one of over 400,000 Americans lost in World War II.

The John Basilone Parade

Each year in September, the John Basilone Parade, billed as the only annual parade in America honoring a war hero, is held in Raritan, NJ. The parade culminates with a ceremony at the John Basilone Memorial Statue. The Raritan Public Library also has a John Basilone Museum with digital archives that can be accessed at raritanlibrary.org

The Devil was let loose in the Neighborhood: Part 1

By C.G. Wolfe / © The Black River Journal 2004

It seems that everyone in the vicinity of Changewater, New Jersey, knew that John Parke had money - lots of it. The question still being asked today though, is who wanted it bad enough to slaughter four innocent people…

John Parke had a good head for business, a trait he came by as a young man when his father died and left him to help his widowed mother Mary raise five younger brothers and sisters. Using money he collected from his father’s outstanding invoices, he began buying and selling real estate up and down the Musconetcong River. When he reached his mid-twenties he was already making a handsome profit. He quickly became a prominent land-owner and added to his fortunes by lending money to friends and neighbors and collecting it back with interest, a common practice in the years before every community had a bank.

Parke took his role as surrogate father seriously, which maybe the reason he never married and started a family of his own. After his mother died, he elevated himself to the head of the household and saw to it that his siblings got a solid education and a good start in life. His brother David became a shoemaker in the nearby village of New Hampton. He married and had nine children but was left a widower when his wife Elizabeth died in 1827. His brother Abner also married and owned a farm across the river in Hunterdon County. He and his wife Lydia had six girls, one of which died in infancy. Two years after his brother David lost his wife, Lydia died. Like his brother, Abner never remarried and raised the children on his own.

Sarah Parke, the eldest Parke girl, never married and kept house for John on his farm in Changewater. Maria, the “baby” of the family also lived in John Parke’s house in Changewater along with her two little boys, Victor and John P., her three year-old daughter Maria Matilda, and her husband John Castner. Castner and a hired boy named Jesse Force, who also resided in the Parke house, farmed the property for John Parke along with 40 adjoining acres that Parke had sold to Castner. John Parke’s middle sister, Rebecca, married a farmer named William Hulshizer. They had one child that survived, a son named William Harris, and they lived less than three miles away near the village of Port Colden

When John Parke turned 56 years old, he decided to make out his will. Over the years he had acquired two farms of over 100 acres each; the farm in Changewater where he lived and the “Meeting House Farm” (named for its proximity to the old Mansfield church), which he rented to his niece Olivia and her husband Joe Carter. In addition to the farms, he owned and co-owned several smaller pieces of property for which he collected rent. He also had more than $10,000 out on loan and at least $5,000 in cash tucked away at the house.

After dividing up his estate, he called his family together and, in an odd gesture, revealed its contents at the gathering. All five brothers and sisters and most of their families would profit from John Parke’s demise. The only exception was his sister Rebecca’s husband, William Hulshizer, who was singled out in the will to receive nothing. “I give and bequeath unto my sister Rebecca Hulshizer one hundred dollars per year…during her natural life and at her decease to end and to be paid only to her since I consider her husband my enemy and unworthy of enjoying any part of my estate.” (In reality though, a wife had very little rights to property in the 1840s and Hulshizer would have profited directly from Rebecca’s inheritance as well as the inheritance of his minor son, William Harris. John Parke considered Hulshizer a man of “low character” and tried in vain to dissuade his sister Rebecca from marrying him. Hulshizer knew about Parke’s feelings towards him and their relationship continued to sour.

The public airing of John Parke’s will probably didn’t help matters and it may not have been the only shot Parke had fired at Hulshizer during their family feud. In 1839 Parke lured away Hulshizer’s farmhand, Joe Carter, by offering him a better deal. Carter, who was married to John Parke’s niece Olivia, had been working for Hulshizer for a year when Parke offered to rent him the “Meeting House Farm” for a share of the crops Carter raised. Carter accepted, though he would never make a go of the place and ended up in serious debt.

Hulshizer’s reputation was further tarnished by his association with a local character of ill repute named Jesse Tiger, who is described in one published account as a “drunkard” and a “chicken thief.” Joe Carter recalled that one day, while riding to town with Henry Hummer, they saw a body lying face down in a ditch alongside the road. It turned out to be a very inebriated Jesse Tiger. Carter didn’t know Tiger personally, only by reputation. None the less, he and Henry Hummer helped him to his unsteady feet and Joe Carter invited him to go up to the house for a cup of coffee and something to eat.

I Have Lost Faith in All Mankind

In 1843, John Parke turned 61 years old. Though he was still the first man people in the area thought of when they needed a loan, it appears that he was growing weary of the business and that it may have left him a bit jaded after all those years. One night Joe Carter went to see him, hoping to borrow fifty dollars. Parke turned him down but went on to reassure Carter that he could stay on at the Meeting House Farm as long as he (Parke) was alive. (After John Parke’s death the farm would be turned over to Sarah Parke, who was given life rights to the property.) He also reminded him that he had provided a nice inheritance for Carter’s wife Olivia, who was one of Parke’s eighteen nieces and nephews. But Joe Carter didn’t have time for John Parke to die. He was already seriously in debt and had recently escaped foreclosure by making a deal with the sheriff on the same day his property was scheduled to be sold at auction. Still, Parke refused, he told Carter that he had the money but wouldn’t give it to him because he “had lost confidence in all mankind, but John Castner.”

Castner was an honest, hardworking farmer, who unlike Carter, was turning a profit for Parke. He never went to bed without adding detailed records of the day’s business to his meticulously kept ledgers. Castner was also aware that attempts had been made to rob John Parke in the past and he was very protective of the household. Sarah Parke stated that Castner kept weapons, including a loaded pistol, a hammer, and an axe, stashed around the house for defense. It was also well known that Castner locked up the house securely every night and never opened the door for strangers. In fact, the night Joe Carter went looking for his loan, Castner refused to open the door until Joe put his face to the window so Castner could be sure it was him. “Joe, I believe it’s you,” he decided after a while and finally opened the door.

On the evening of May 1, 1843, John Parke finished his dinner and headed upstairs to bed. It had been a fairly typical day. He spent much of the afternoon talking with his friend, Jacob Skinner, who was a frequent visitor to the Changewater farm. George Martenis stopped by to ask for a fifty dollar loan but Parke refused him. Jesse Force, John Castner’s hired hand, was tired from a long day in the fields and decided to turn in too and went upstairs shortly after Parke did.

Sarah Parke was away from the house at night for the first time in several years. That day John Castner brought news that her sister Rebecca’s son was very ill and not expected to survive. John Parke suggested that Sarah go over to the Hulshizers’ and help Rebeeca with her sick little boy. She left before sundown and walked the two and a half miles to the Hulshizer house.

Maria Castner put her two boys, Victor and John P. to bed, tucking them in for the night. She cleaned up the dinner dishes and then went to the bedroom to put the baby, Maria Matilda, to sleep and get ready for bed herself. John Castner, as was his habit, lit a candle, sat down at his desk, and began scratching figures into his ledger books.

Around nine o’clock, there was a knock at the door. John Castner instinctively reached for his pistol and shouted, “Who’s there!” A friendly voice answered back. Castner peered out the window and squinted into the darkness. Recognizing a familiar face, he finally opened the door… Shortly after nine, Eliza Case, who cooked for the hands at the nearby Franks & Strader grist mill, was slopping the hogs when she heard a distant holler in the direction of the Parke farm. She stood very still, tilted her head, and listened again, but everything was quiet now.

A Murdered Man at the Bottom of the Sink Hole

It was around 5:30 on the morning of May 2, 1843, when Stacy Bowlby crossed the rain-swollen Musconetcong on his routine trek to Port Colden. As he passed John Parke’s house he came in to view of what was now becoming a familiar landmark, a six-foot deep sink hole in the road. Joe Carter, who was in charge of the roads, had talked to John Castner about filling it in but nothing had been done yet, except that Castner had marked it with a few fence posts to warn unwary travelers. As Bowlby approached the hole this morning however something odd caught his eye.

It was the muddy, battered body of a man, lying face down at the bottom of the hole. His head was caked in blood and one of the fence posts that had been used to mark the sink hole lay across the side of his face. Scared out of his wits, Bowlby ran to the nearest house for help – the home of John Parke. He banged wildly on all the doors but no one answered so he made a frantic dash to the Franks & Strader Mill. At the mill he found James Petty and Peter Vanatta and with what little breath he could muster shouted that there was a murdered man at the bottom of the sink hole!

Petty and Vanatta gathered up several more men from the mill and headed up the hill towards the sink hole. When they arrived and looked down upon the gruesome discovery, James Petty recognized the battered corpse and knew immediately that it was John Castner. Unsure of what to do, Petty sent for George Franks, who was known as a “decisive and deliberate man.” Franks arrived and immediately sent men to get William Prall Esq., Jacob Arndt, a local justice of the peace, and constable Robert Vanatta.

After looking around some more, Franks and the men at the sinkhole noticed footprints heading up the road toward Port Colden. They followed the tracks some 45 feet beyond the sinkhole and found blood stains and signs of a struggle on the ground where the tracks abruptly ended. They also found long skid marks leading back to the sink hole. It was clear that the killer began his assault on Castner at the bloody spot in the road and then dragged his body to the sink hole and threw it in. It also appeared that the killer, perhaps seeing that poor John Castner wasn’t quite dead, bludgeoned him mercilessly with one of the fence posts.

After William Prall, Esq. arrived and examined the scene, Bowlby told him how he had gone to the Parke house when he first discovered the body but that no one had answered the door. Prall left several men behind to guard the crime scene and headed off with the rest to John Parke’s house. They banged on the doors once again and when no one answered they tried the knob and found the door was unlocked. They entered the house, which was ominously silent. The carnage they found inside overwhelmed their Victorian senses.

They discovered Maria Castner first. She was lying face up on her bed her legs dangling lifelessly over the side. She was partially undressed, as if in the middle of getting ready for bed and she was clutching a candle in her left hand. Her 3 year old daughter Matilda was laid across her body. They were both dead and had a large puncture wound near their temples. The killer had taken the time to cover them with a blanket and put a pillow over Maria’s face, as if he couldn’t bear to look upon his own butchery.

Then they climbed the stairs to Jesse Force’s room and found the seventeen-year-old farm hand lying in bed propping up his bloody head with his hand. He had also been savagely assaulted but he was still alive. Prall immediately sent James Haslet to get Dr. McClenahan in New Hampton. Jesse Force would survive but the severity of his condition left him with no memory of the attack.

They went to John Parke’s room next. Parke was laid out “perfectly straight” in his bed. He was face up and like Maria Castner a blanket was pulled up to his chin and his head was covered with a pillow. One of the men sheepishly pulled it aside. Like the other victims, Parke had been struck in the head repeatedly with a devastating instrument but the viciousness of the assault seemed even more violent than the others. Parke’s head was completely shattered and he had been hit with so much rage that part of his skull was protruding out above his ear.

At this time someone nervously asked where the Castner boys slept and George Franks’ wife, Ann, who had just arrived, directed them to a small room off the parents’ bedroom. Miraculously, nine-year-old Victor and six-year-old John P. were untouched and slumbering innocently in their beds. They never woke during the murderous rampage and had no idea what had occurred while they slept. The only other member of the household to survive was Sarah Parke, who either by providence or coincidence, had spent the night at William and Rebecca Hulshizer’s house, and escaped the others’ fate.

Joe Carter and Peter Parke

Men took off in every direction to spread the alarm that a killer (or killers) was on the loose. Neighbors began showing up to view the grisly scene and soon hundreds, including reporters from all over the state, descended on the village of Changewater.

John Parke’s nephew, Peter Parke, was working in his shoe shop in New Hampton when Lyndon Lyman came in with the stunning news around 7:40 that morning. Accounts say Pete slumped into a chair and shook his head slowly in disbelief. Gathering his composure, he grabbed his coat and headed off to tell Joe Carter and his wife Olivia before heading to Changewater.

Pete reached the Meeting House Farm around 8:15 a.m. and told Olivia what he had heard about their “Uncle Johnny,” cousin Maria, her husband John Castner and their daughter Maria Matilda. He then walked down to the field where Joe and his cousin, Henry Hummer, (Carter employed Henry as a farm hand) were plowing and broke the news to them. Henry said that he didn’t believe it and went back to work. Joe Carter was skeptical as well but decided to accompany Pete to Changewater to see for himself.

They unhitched the horses from the plow and rode bareback to Changewater. On the way they ran into Charles Rounsavell, who told them that the news was true and that he had seen the murder site with his own eyes. They rode on to the sink hole, where a small crowd had already gathered to view the tattered remains of John Castner. After seeing the body themselves, they talked with some of the folks that were milling about. Around ten o’ clock, a party of men arrived and removed Castner’s corpse from the mud and blood-soaked hole. They placed him gently into a wagon and brought him to the house. Later that day, a group of stoic neighbors washed and dressed the bodies of their murdered neighbors and laid them out in the parlor of the Parke home.

Joe and Pete walked down to the Parke house, where an inquest jury was already viewing the crime scene. Joe went into to have a look but Pete didn’t think he could handle it and stayed outside. Joe came out after a few minutes and told Pete what he had seen. They walked a short distance from the house and Pete sat down on the grass. Joe left him there and headed home.

Pete’s father, David Parke (John Parke’s brother) saw his son sitting dejected near the house and went over to console him. David told Pete that he was going to have Joe Carter clean the old church at the graveyard in case it was going to be used for the funeral and asked if he would help. Pete said he would and after they talked a while he decided to go home. When he got back to the house and the shoe shop, he told everybody except his wife Rachel what had happened. Rachel had been sick lately. He asked the doctor to come by that afternoon and thought it would be better to wait until then to tell her the heart-breaking news.

Joe Carter got back from Changewater around noon and told Olivia and Henry Hummer that the sad news was true and described the scene for them. He told them it was the most horrible sight he had ever seen his life. After lunch he rode over to Cornelius Stewart’s store. Stewart and Carter did a lot of business together and Stewart always extended Joe a generous amount of credit. Outside the store, he was confronted by a constable from Greenwich Township named John Segreaves. Segreaves had a foreclosure against him for $61.75 and was there to collect the money or confiscate his personal property. To Segreaves’ surprise, Carter offered him $45.00 in cash and told him he’d pay him the balance of the loan the following week. Segreaves reluctantly agreed and gave Joe a receipt for the payment.

The morning after the bodies were discovered, Joe Carter and Peter Parke met to clean the old church at the Mansfield cemetery. While they were working, Joe told Pete that he had purchased a thresher for the farm and gotten behind on payments. He said that he was being foreclosed on and had to appear before Squire Howell in Philipsburg the next day. According to Joe, the Squire would hold off the proceedings if he could get one of three men, Jacob Davis, George Creveling, or Imla Drake to sign as security for the loan. When they were finished at the church, Joe went to see Jacob Davis but Davis turned him down and suggested he go ask George Creveling. The only problem was that Joe already owed Creveling money on another loan. So to better his chances, he paid Creveling $10.50 on the old debt before asking him to sign the security note. Creveling turned him down anyway.

Joe decided to go see Imla Drake and stopped by Stewart’s store on the way. There he ran into Constable Robert Vanatta, who held four foreclosures against him. Joe asked him to step outside and then paid him $20.00 cash against the loans and told him he’d pay off the balance very soon.

Joe caught up with Imla Drake at Abram Cougle’s blacksmith shop but Drake told him he was short of money himself right now and couldn’t help him. So Joe went back to Jacob Davis and asked him one more time. Davis finally agreed and told him to come by in the morning for the papers. Joe was relieved but still wouldn’t be able to get the note from Davis in time for court.

He decided to write Squire Howell a letter and went over to Pete’s shoe shop to get a piece of paper. He wrote Howell that he couldn’t make it to court due to all the confusion over the murders and that if the Squire would give him two more weeks, he would come pay off the loan. He read the letter to Pete and had him write out the address, since his penmanship was better than Joe’s. Abram Cougle was making a regular trip to Philipsburg the next morning and agreed to deliver the letter to Carling’s Tavern, where the squire held his court. Carter brought him the letter early the next morning.

The Guilty Parties Stood Among Them

On Thursday, May 4, Peter Parke estimated that three to four hundred wagons were already at the Parke farm when he arrived for the funerals. The family had anticipated the crowd and decided to hold the service beside the orchard in back of the house. After the sermon, the funeral procession would go out to the Mansfield Cemetery for the burial.

At one time, everyone had attended the old church at the cemetery, but when new churches were established in both Washington and Bethlehem Township, the congregation was split. Now each member attended the church they lived closer to, so to satisfy both sides the reverends from each church, Reverend James Lewers and Reverend Jacob Castner, were invited to speak at the funeral.

The sermon at the orchard lasted two hours but it was the oration that Reverend Castner gave later on at the cemetery that most folks remembered. Castner told the crowd that he was convinced someone in the Parke family had committed the murders for the inheritance and told them that God had chosen him personally to find the killers. He further insinuated that the guilty parties stood among them and encouraged them to look closely at their friends and neighbors. Castner’s venomous tirade, particularly his attack on the Parke family, caused many in the crowd to flinch in discomfort but others heeded his call to action.

When Castner was finished, John Parke, John Castner, Maria Castner, and Maria Matilda Castner were finally laid to rest. For many the sight of only three coffins and three graves was more than they could bear - little Maria Matilda was going to spend eternity in her mother’s arms.

Willful Murder

The jury of inquest ruled that the deaths were the result of “willful murder by a person or persons unknown.” It was believed that John Parke was the primary target. The prevailing theory was that between 9:00 and 10:00 on the night of the murders, someone who knew John Castner lured him out of the house and got Castner to accompany him (or them) up the road, approximately 45 feet past the sink hole. A severe wound to the back of Castner’s head suggests that the killer then struck him suddenly from behind and attacked him with a double-sided weapon, like an ice axe. (Even though there were gash wounds consistent with a hatchet and deep puncture wounds like those that might be inflicted with a large pick, the prosecution believed that a single weapon had been used on all the victims.)

The killer then returned to the Parke farm and it is believed that Maria Castner opened the door and let him (or them) in to the house. Maria and little Maria Matilda were killed in the Castners’ bedroom and their bodies were thrown onto the bed and covered up with a blanket and pillow. They each had a puncture wound near the temple and the examining doctor believed that Maria Castner may have also been strangled.

The intruder then made his way up the stairs to the second floor towards John Parke’s bedroom. Jesse Force may have woken at this point and stirred to see what was going on. The intruder struck him three times in the head, fracturing his skull, and Jesse feel back on to his bed. The killer then entered John Parke’s room and murdered him as he lay sleeping - the attack was particularly savage. Like Maria and the baby, the killer then covered him with a blanket and pillow.

Further investigation found that besides the murders, the rest of the house was undisturbed; no locks had been broken open and no drawers or chests appeared to have been searched. It also found that very little if any money had been stolen, even though John Parke had $5,625 in paper, gold, and silver hidden in various places throughout the house, including $3,000 in a chest at the head of his bed and $175 in an unlocked drawer of his desk. The apparent lack of a robbery led many to believe that the motive for the heinous killings must have been the inheritance.

There were no witnesses to the crimes but several people in the village of New Hampton reported that around 9:00 on the night of the murders, they heard a horse and wagon cross the bridge near Simonton’s Mill and turn towards Changewater. Besides the crime scenes, the only other physical evidence that was attached to the murders was discovered by John Smith, a wheelwright and wagon maker from New Hampton. Smith remembered that on the day of the murders he saw fresh horse and wagon tracks between the sink hole and the Andersontown road intersection. After thinking about it for a while, he decided that the killer may have approached the Parke farm from the Hunterdon County side of the Musconetcong River. There were two places he knew of where you could tie a horse and wagon and cross the river on foot --Changewater Ford, at the bottom of a path near the Parke farm, and a place called Rounsavell’s foot log.

The day after the funerals, Smith went back to Changewater to look around and found exactly what he was looking for. Approximately 15 to 20 feet from Rounsavell’s foot log, there were imprints in the ground that looked like a horse and wagon had been parked and stood for a period of time. Smith mentioned his discovery to David Parke the following day. At first David Parke believed Smith might have stumbled on to a vital clue but then he thought he remembered a horse and wagon being tied at that very spot on the day of the funeral and dismissed Smith’s discovery. (Continued in Part 2)

Photo by Lee Wolfe

The graves of John Parke, Maria Castner, Maria Matilda Castner (Maria Matilda was buried in the coffin with her mother), and John Castner.

"In My Dutch Bible..."

By C.G. Wolfe / © The Black River Journal 2017

It left New Jersey in a covered wagon, and after thousands of miles, a dozen generations, and more than two centuries, it came back in an R.V.

It was the cusp of the summer season at Melick’s Town Farm in Oldwick, New Jersey. Counters were flush with ripe, red strawberries, and thick spears of asparagus stood green and tall in a tub of cool water. Rebecca Melick was managing the market that weekend. A youthful vegetarian whose pet pig Winston has become a regular attraction at the farm store, Rebecca and her brothers, Peter and John, represent the tenth generation of a farming family whose Hunterdon roots reach back more than 300 years to their ancestor Johan Peter Moelich, who arrived in Philadelphia on August 14, 1728 aboard the ship Mortonhouse and eventually made his way to New Jersey. (It was common in the German tradition to bestow a child with two given names at their baptism. The first name was a spiritual or saint’s name. The second name, or “rufnamen” was the name the child was known by. The spiritual name was used repeatedly and usually given to every child of that gender in the family. Thus, Johan Peter and his brother Johan Gottfried were simply referred to as Peter and Gottfried, as we will do in the remainder of this article.)'

Like many of the early German settlers of his era, Peter Moelich, came from the strife-riven Middle Rhine region of Germany, which included the fragmented Holy Roman territory of the Palatinate. Peter and his brothers Johannes and Gottfried, who would follow him to the colonies in 1735, were probably spurred by the success stories of other adventurous German Palatines, as they were known, who fled the war-torn provinces of their homeland to escape religious quarreling, onerous taxes, and a rash of harsh winters and failing crops. Responding to an invitation from the sympathetic government of Queen Anne for passage to the North American colonies in exchange for work, ships packed with Palatine refugees poured into the docks of London in the spring and summer of 1709. In 1710, the English transported almost 3,000 immigrants in ten ships to the colony of New York. While many of these new arrivals settled along the banks of the Hudson and in New York City, some families headed for the Jerseys, where they established the oldest Lutheran churches in the state, including Zion Lutheran in Oldwick, Hunterdon County (the oldest Lutheran Congregation in New Jersey, which dates to 1714), and Raritan-in-the Hills in Pluckemin, Bedminster Township, Somerset County.

Tewksbury and Bedminster Townships have become the hub of Melick (or depending on the era, geography, or accuracy of the census taker, Malick, Mellick or Moelich) history, and each year amateur genealogists from far and wide follow the branches of their family trees to Zion Lutheran in Oldwick, the old cemetery of St. Paul, and Johannes Melick’s stone homestead outside of Far Hills, in Bedminster Township, which was made famous by Andrew Melick, Jr.s 1889 book, The Story of an Old Farm.

“Every summer somebody shows up from Timbuktu and the guy says (it’s mostly guys), ‘Guess what? My name is Melick.’ I’ve had a federal judge, I’ve had a concert pianist, I’ve had numerous other people that stick out in my mind,” said family patriarch, George Melick of Oldwick. “Somebody shows up here and wants a guided tour and I’m always happy to do it.”

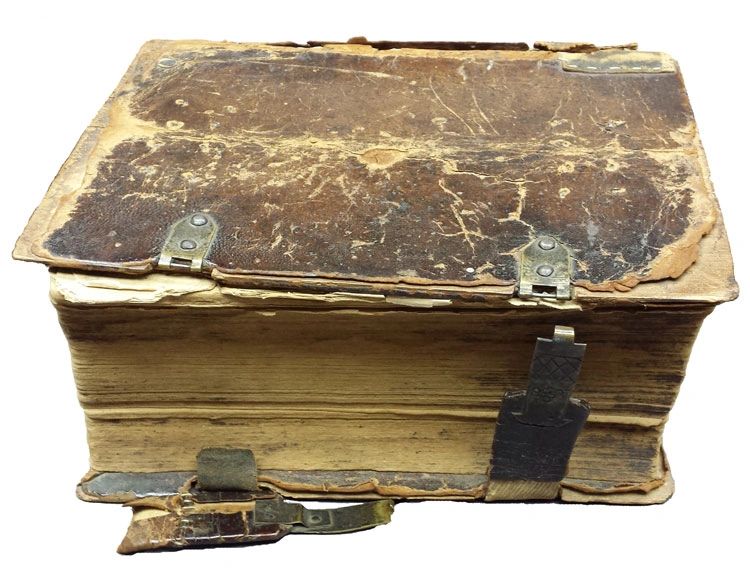

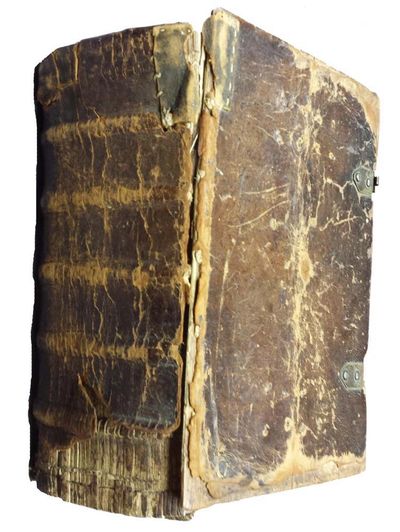

This summer however, when an R.V. with out of state plates rolled into the Melick Town Farm Market, and one of the occupants asked to see a member of the family, and found Rebecca Melick, it wasn’t someone looking for a tour (and it wasn’t a guy). It was a woman named Andrea Harte, a distant relation and a direct descendant of Peter Moelich’s brother, Johannes (The Story of an Old Farm). Andrea and her husband had traveled all the way from Butte, Montana with a 273-year old, rare, first edition Sauer Bible. The German-language bible had been given to Johannes’ son Philip on his wedding day and for the next two-and-a-half centuries had migrated with family members on their journey west until finally reaching “Big Sky Country” in Montana.

Andrea received the family bible from her uncle, J.W. Malick, “I need you to take it and I need you to make sure it never leaves the family,” he told her. Years later, with no one in her direct family line to entrust with the bible, Andrea began searching for the bible’s next beneficiary. After exploring places in Ohio and West Virginia, she discovered her distant relatives in Oldwick, New Jersey.

“I wanted an heir with the Melick name,” she said. “I felt that was where it belonged.”

So Andrea and her husband placed the bible in their R.V. and headed east, stopping along the way to let other relatives see the family heirloom before it left her hands, but the bible’s circuitous journey home actually began centuries before Andrea was entrusted with it.

Philip Moelich (1736 - 1797) married Mary King on April 14, 1762. Philip and Mary resided in the village of Pluckemin at the time of their marriage, and it is assumed that they took their vows there, at St. Paul’s Church. The bible was a gift from Philip’s father in-law, David King, and notes in both King’s and Philip Moelich’s hand, recording family births and deaths, are scrawled along the blank pages. In 1787, Philip, along with the family of his firstborn son, John (1762-1844), who married Mary Todd at Zion Lutheran Church in Oldwick, in 1781, and apparently began spelling his last name “Malick,” left the blue hills of New Jersey for wilder regions in the Eastern Panhandle of what is now West Virginia, settling along Opequon Creek, a 64-mile tributary of the Potomac in Berkeley County. A testament to the hardships of the era is evident in a particularly poignant entry in the bible that must have been added shortly after their arrival in Berkeley County, which reads: “October ye 7, 1787 then departed this life marey melick the daughter of philip melick and was 21 years and four months… She dide in new virginnia at opaken crick and was buried near Sulfer Spring.”

In 1797, the year that Philip Moelich died, John moved his family again, taking the family bible with him to Hampshire County, some 50 miles from Berkeley. A veteran of the American Revolution, John served eight months as a private in the New Jersey Militia, participating in the battles of Springfield and Short Hills and patrolling the countryside during the revolt of the Pennsylvania Line at Jockey Hollow. When he applied for his pension in 1833, he stated that he was born in Bridgewater, Somerset County, in New Jersey, on 11 January, 1762. When asked “Have you any record of your age, and if so what is it?” He replied, “Yes. In my Dutch Bible which belonged to my father and grandfather.”

John Malick died in 1844, and is buried at the Malick Family Cemetery, a rural, one-acre graveyard off of Rte. 29 in Augusta, West Virginia, on land that once belonged to his son Aaron. Following tradition, the bible should have passed to John’s eldest son, Philip B. Malick (1788-1885) but under somewhat mysterious circumstances it ended up in the hands of his youngest son, Uriah, as chronicled in a letter to him from his brother Aaron, in May of 1876. It reads in part: Dear Brother and Family, I have taken all the record off that I understand. The Bible has been very much abused since it left the family of Malick. I mended the back the best I could, And now Dear Brother I Present to you to be kept in the Malick family. I shall Express it to you as soon as I get word from you your nearest Express Office…”

Finding the nearest Express Office to his brother Uriah may have proved a challenge. After relocating to Clinton County, Ohio, in 1832, where he resided for over thirty years, Uriah Malick headed west, arriving in far-off Milford, Nebraska in 1866; a prairie town near the ford of the Big Blue River and the “Indian healing springs,” in Seward County. At the time Aaron would’ve shipped the bible west, the railroad hadn’t reached Milford, although a road had been built for the wondrous, new “Steam Wagon” (see paragraph at the end of the article) that had arrived in Nebraska City in 1862. The steam wagon never came to Milford, but the improved road brought travelers and freight wagons, and the bible, which arrived in Milford during the calamitous “Grasshopper Plague,” probably came by stage.

Uriah Malick sold his land in Nebraska and moved to Dewitt, Arkansas in 1880, where he resided until his death two years later. Uriah Malick’s son, Dr. Uriah Horseman Malick, who practiced as a physician and surgeon in Bloomington, Nebraska, inherited the family bible, marking his ownership with a bookplate on the end paper, of the front cover. The bible was passed to Dr. Malick’s son, Jesse Uriah, who gave it for a time to his daughter Eloise, before it eventually was given Jesse Uriah’s son, Jesse Waldeen (J.W.). Upon his death, J.W. entrusted it to his sister Eloise’s daughter, Andrea Harte of Butte Montana.

“This must have left in a covered wagon, and it came back in a motor home,” said Rebecca Melick, as we sat in a room at Zion Lutheran Church in Oldwick, with her father, George, and Zion’s Pastor, Reverend Dr. Mark R. Summer, looking at the weighty tome in the center of the circular table. The handwritten notes inside are the record of a family’s American journey that only hint at the tales the pages could tell if given voice. Stories of love and joy, despair and hard times, faith and redemption. It had taken 229 years for the bible to come back home to New Jersey and the good book was showing the scars of its travels and “abuses;” a leather patch sewn into the cover, the spine loose and tattered, and a tin plate with blacksmith rivets holding the halves of a split board together, no doubt the “mend” that Aaron mentioned in his 1876 letter. Yet through the generations of hands it passed through, each family member did their best to preserve its legacy, even, as Rebecca Melick noted, long after anyone in the family could read its German text. Now another branch and another generation of the family have inherited the responsibility of, not just preserving its heritage, but continuing the story.

THE STEAM WAGON

Weighing ten tons with back wheels that were ten-feet and two-inches in diameter, Joseph R. Brown’s smoke-belching behemoth was the first self-propelled land vehicle west of the Missouri River. Coming all the way from New York City, and purportedly tested in the hills of New Jersey, the Steam Wagon arrived in Nebraska City by steamboat on July 14, 1862. Operated by a three-man crew and able to pull four or five wagons, Brown envisioned a fleet of steam wagons running between Nebraska City and Denver, bringing supplies to the gold rush fields of Colorado. The steam wagon arrived with great fanfare and made several excursions around the city before setting out on its much-hailed maiden voyage to Denver, on July 22. The “Prairie Wagon,” as it was dubbed by Nebraskans, made it less than two miles from the town when it started having mechanical problems and eventually completely broke down. Undeterred, Brown left Nebraska promising to not only fix the broken steam wagon but bring a fleet with him on his return, but on August 17, a Dakota hunting party attacked settlers in Southeast Minnesota, igniting the Dakota War of 1862. Brown rushed back to his home in Minnesota, to discover that his wife and children were taken prisoner. His family was later rescued but Brown accepted a commission in the Army and served until 1866. Brown’s representatives, including the Steam Wagon’s builder, John Reed, returned to Nebraska City to keep his venture alive. The steam wagon was repaired and had one last, brief hurrah during a Fourth of July parade in 1864, before breaking down again and being hauled off to a farm field outside of town, where it remained, abandoned and rusting, until it was dismantled for scrap in 1889.

The Sauer Bible

Born in the German Electoral Palatinate in 1695, Christophe Sauer (1695-1758) arrived in Philadelphia with his wife Marie and only child, Johan Christophe, in the autumn of 1724...

The Sauer Bible

By C.G. Wolfe

Born in the German Electoral Palatinate in 1695, Christophe Sauer (1695-1758) arrived in Philadelphia with his wife Marie and only child, Johan Christophe, in the autumn of 1724. A tireless entrepreneur with mechanical aptitude and an inquiring mind, Sauer, at various (and simultaneous) times, was a tailor, farmer, apothecary, performed surgeries and bloodlettings, clock maker, cabinet maker, glazier, and by 1738, had determined to become a printer, a profession that usually took years of apprenticeship. Through connections in Germany he obtained a set of Gothic (Fraktur) type and instead of importing a printing press, built one himself. Putting his experience as an apothecary to use, Sauer used lampblack to concoct his own ink for the press, which he later marketed as “Sauer’s Curious Pennsylvania Ink-Powder.” Procuring paper, a scarce commodity in the colonies, was Sauer’s greatest challenge and he initially turned to fellow printer, Benjamin Franklin, who sold him paper on credit at wholesale.

Sauer was eager to offer German-speaking colonists printed material in their own language and from his press in Germantown, he was soon producing hymnals and religious texts, as well as a newspaper and popular almanac. He is probably best-remembered however, for his German bible, "Biblia, Das ist: Die Heilige Schrift Alten und Neuen Testaments, Nach der Deutschen Übersetzung D. Martin Luther." (Bible: The Holy Scripture of the Old and New Testaments following the Translation of Dr. Martin Luther), which was the first European-language bible in America. The son of a Reformed minister, Sauer was keenly interested in religion, particularly the separatist views of the Pietists, a movement within Lutheranism that stressed individual piety and living an evidential Christian life over religious formality and orthodoxy. Published in 1743, Sauer printed 1,200 bibles which he sold unbound or bound in calfskin with metal fittings, by the Brethren at the Ephrata Cloister in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. A hefty tome, the full version of Sauer’s bible ran to 1,284 quarto-sized pages.

Ironically, Sauer’s bible was met with opposition by many Lutheran and Reformed clergy who took umbrage with his sectarian views and what they considered an anticlerical editorial bias in his almanac and newspaper, as well as his addition of several books from the Berleburg Bible, considered a radical Pietist translation of Martin Luther. Influential church leaders, such as Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, who would become known as “the patriarch of the Lutheran Church in America,” discouraged parishioners from buying Sauer’s bible. (Muhlenberg preached many times at Zion Lutheran, in Oldwick, NJ and resided in the village for nearly a year in 1759-60.) It took almost twenty years for Sauer to sell his unsubscribed copies of the 1743 bible, but despite its initially slow sales, Christophe Sauer’s German bible grew in popularity prompting his son to publish second and third editions in 1763, and 1776.

Political Graveyard: Two Presidents – One Grave

By C.G. Wolfe © The Black River Journal

Among a bevy of political, religious, and military New Jersey notables buried in the Princeton Cemetery, on Greenview Avenue, in Princeton (including Aaron Burr, who is mostly remembered as the sitting Vice President who killed the musically-celebrated, Alexander Hamilton in a famous duel), is the grave of President Grover Cleveland, the only New Jersey native to be elected President of the United States.

Stephen Grover Cleveland (he later dropped the Stephen) was born in Caldwell, NJ in 1837, but was reared in upstate New York, where his political career began. A Democrat elected in an era of Republican domination of the White House (Cleveland was one of only three Democrats elected president from 1861- until 1933), Cleveland was known as a reformer who fought political corruption and patronage, and a laissez-faire, pro-business politician who favored the gold standard, low tariffs, limited tax and spending, minimal government interference, and military non-intervention. In his 2013, biography, author John Pafford calls Cleveland “The Forgotten Conservative.”

Cleveland was the only president who was a bachelor when he took office, and the only president to be married while in the White House, when he wed 21 year-old Frances Folsom, the youngest first lady in history. Among his other firsts, Cleveland was the only president to be elected to two non-consecutive terms. Winning the election of 1884, but losing his reelection bid in 1888 against Benjamin Harrison. (Adding once again to his list of possible topics of trivial pursuit, Cleveland won the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College vote, putting him alongside Andrew Jackson, Samuel Tilden, Al Gore, and Hillary Clinton.) Cleveland returned to the political arena and won his rematch against Harrison in 1892, making him the 22nd and 24th Presidents of the United States.

So, while he is only one man, the case could be argued that two presidents are buried in New Jersey.

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.